What is Diastasis Recti and How to Avoid it During Pregnancy

Expert advice on how to safely and effectively protect your core during pregnancy, plus tips for healing postpartum.

Medical Expert: Becca Sanders Fung, DPT

When I was pregnant with my first baby, I was certain I would snap back to my pre-baby self postpartum. After all, I had been a lifelong athlete and maintained a healthy and active pregnancy.

But there I was—months postpartum—not feeling anything like my old self again. While the number on the scale matched what it was before I was pregnant, I could not say the same about my physical appearance or abilities. I still had a small bump, but more than that, my stomach muscles were so weak that I could hardly get out of bed.

I had never imagined my body would look and feel like this months after giving birth, and I started to worry. Was this my new normal after baby? Would I ever be able to do heavy lifting at CrossFit again? Or even find the core strength to do a push-up?

After doing some research, I discovered what I was experiencing was not normal. My weak abs and protruding tummy were a symptom of abdominal muscle separation known as diastasis recti.

What is Diastasis Recti?

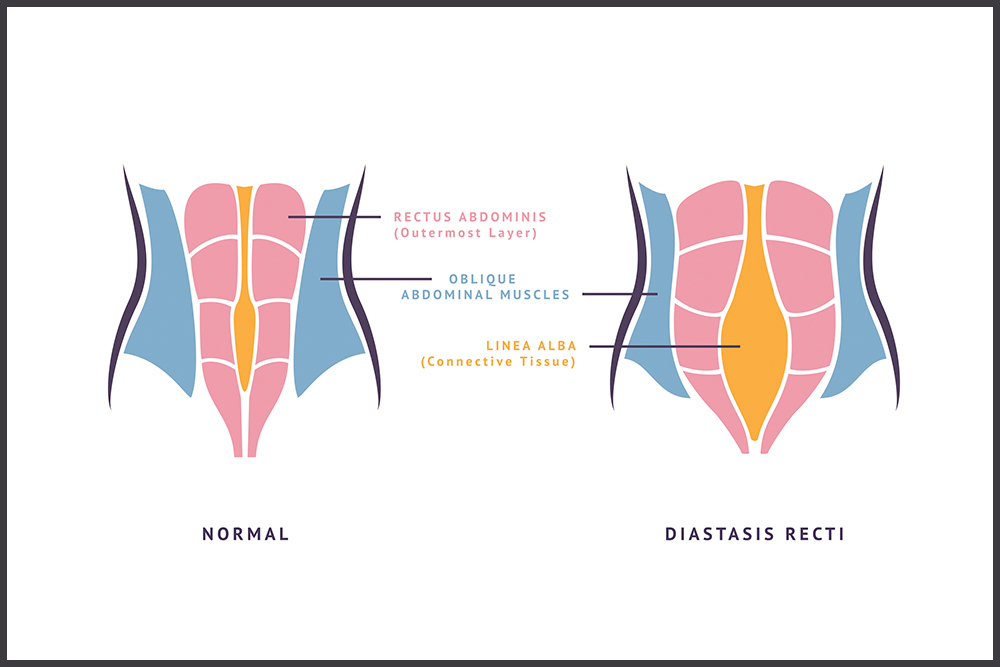

Diastasis recti is a common condition that occurs when the connective tissue that holds together your rectus abdominis muscles (aka your six-pack muscles) separates. This separation is not painful, but it can lead to many undesirable side effects, including abdominal weakness, belly pooching, lower back pain, and urinary incontinence—symptoms birthing parents have come to accept as standard to the postpartum body.

This condition affects 60% of birthing parents and usually clears up within eight weeks of delivery. However, around 40% of those affected by diastasis recti continue to experience symptoms six months postpartum—and possibly longer. These lingering symptoms are not only unpleasant, but they’re also not ordinary.

According to Becca Sanders Fung, DPT, a certified prenatal and postpartum physical therapist in San Fransisco, California, “Many birthing parents have been told that it is normal to have a pooch around their midsection or even incontinence when you laugh or run after baby. Although these things are common, they are not normal and are signs of an underlying dysfunction.” Because diastasis recti itself is painless, many birthing parents assume the belly pooch and weakness are routine parts of their new-parent physique.

Though often confused, diastasis recti differs from a hernia, and both require distinct treatments. While the separation of abdominal muscles signifies diastasis recti, the fascia of the wall (the connective tissue beneath the skin) stays intact. With a hernia, an actual hole or defect forms in the fascia and requires surgery for full closure.

How to Tell if You Have Diastasis Recti

This quick trick can be done after both cesarean and vaginal deliveries to determine whether or not you’re experiencing abdominal separation.

Lie on your back with your knees bent and your feet flat on the floor. Gently bring your head up into a crunch-like position (keeping shoulders on the floor) and use your fingertips to check for separation. Depending on your finger widths (two, three, or more) will determine how wide the separation is within your abdominal wall.

How to Avoid Diastasis Recti

My new and unfamiliar shape left me feeling confused and frozen, unsure of what would strengthen my abs and what would make the separation worse. But Fung assured me all hope was not lost.

“Birthing parents can definitely get stronger abs and bodies after baby. This can also help them have more confidence in their daily activities—whether it’s running or lifting their kids,” says Fung.

However, a lack of information could lead new parents to unknowingly make the separation worse instead of better. “Traditional core exercises, like crunches and sit-ups, usually won’t make your abs flat if you have diastasis recti,” she explains. “Without the proper progression back to strength, many ab exercises can worsen the abdominal separation by putting pressure on your abdominal connection.”

Still, not all hope is lost. With proper strengthening exercises, good body mechanics, and abstaining from activities and exercises that put pressure on the separation, birthing parents are able to heal their abs and get back to their favorite prebaby activities.

If you’re hoping to avoid diastasis recti during pregnancy, Fung shares some pro tips to help guide your muscle-strengthening routine to ensure it is effective.

Tip: Avoid Crunches During Pregnancy

Crunches are one of the most popular abdominal exercises, but it is best to avoid them during pregnancy. Crunching or piking puts pressure on the linea alba—the connective tissue that holds your abdominal muscles together. This tissue is already under stress from the 40 weeks of growing a baby, and extra stress can increase the chance of tearing the tissue and developing diastasis recti.

Tip: Strengthen Deep Core and Gluteal Muscles

Just because you should be avoiding crunches does not mean you need to completely ignore your core. Rather, focus on the deep core muscles, such as the transverse abdominal and pelvic floor muscles. The transverse abdominis acts as a corset by supporting the core and reducing stress on the abdominal connection. Strengthening gluteal muscles adds support outside the pelvis, too. (Bonus: Working these muscle groups during pregnancy can help with labor and delivery.)

Tip: Roll Out of Bed

Instead of sitting up to get out of bed in the morning (or after a pregnancy nap), start rolling out. To do this effectively, rotate onto your side, then push with your arms to get out of bed. Even though it seems like a small change, the modification goes a long way toward reducing stress on your abs.

Tip: Use Active Posture

We have all witnessed the “pregnant waddle,” with the hand on the back and the belly button protruding forward. This posture actually puts extra strain on your abs by pushing your belly forward. A better way to stand is with active posture, making sure your shoulders are back and your head, spine, and pelvis are aligned (and, thus, so is your midline).

Tip: Commit to a Rehab Program

Labor and delivery cause trauma to the body, and we need to recover in a focused and directed way—just like we do with other injuries under the care of a physical therapist. Finding an expert-guided ab-rehab program will be crucial in strengthening postpartum ab muscles. Look for something that specializes in postpartum recovery that you can trust and commit to it.

What About C-section Deliveries?

Regardless of how baby is brought into the world, diastasis recti is a risk factor for all birthing parents. However, during a C-section, your muscles are stretched further apart than normal because during surgery, doctors usually separate the muscles along the abdominal wall to access the baby versus cutting through the muscle, thus creating more separation. There are different schools of thought on stitching the abdominal muscles back together or allowing them to heal on their own ( sometimes, it depends solely on your individual autonomy).

Before jumping into a postpartum workout routine, it is important to let your body heal for a minimum of six weeks after surgery (some birthing parents need upward of 12 weeks) and discuss a safe and appropriate recovery plan with your health care provider or OB-GYN.

While taking steps to avoid diastasis recti during pregnancy is ideal, it’s never too late to heal your body. Whether you are six months, six years, or even 16 years postpartum, there is a way to train your body and abdominal muscles to be strong again. If a professional athlete sprained their ankle, we would not expect them to limp forever. Similarly, when a birthing parent has a baby, they should not expect to have a weak core and abdominal separation forever. Both simply require the proper therapy, guidance, and exercise—and both can heal.