Why Aren’t People of Color in Medical Illustrations?

When Nigerian med student and illustrator Chidiebere Ibe, 25, began studying medical illustration in July 2020, he quickly realized the blatant lack of diversity in the content he was examining. Throughout his education, he found the learning process difficult due to inadequate representation and believed it was affecting minority groups as well as their quality of health care.

“We are driving toward proper inclusion where everyone receives equal health care,” said Ibe, in an interview with CNN. “If that’s the goal, then what’s the approach to achieving that? If it’s not very inclusive or without proper representation, then how are we walking toward that goal?”

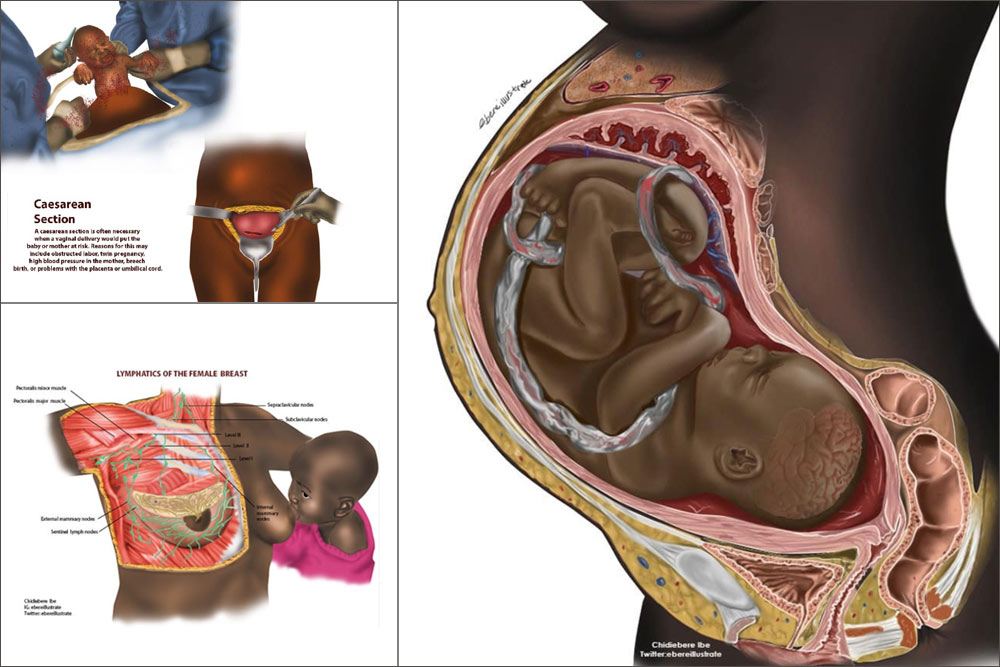

Seeking to advocate for more inclusive texts, Ibe began creating images of anatomy and varying conditions on pigmented skin, including cold sores, blisters, and chicken pox. But it was an image of a black fetus inside a woman’s womb that recently made big waves in Ibe’s now viral Twitter post.

Floods of commenters stated that they had never seen a Black pregnant woman or fetus illustrated before—not in textbooks, doctor offices, pamphlets, infographics, etc. Not only is this shocking, but it sadly points to a much bigger issue of racial disparities in maternal and infant health and pregnancy-related deaths. Proper inclusion is necessary for effective prenatal care and better obstetric outcomes for women of color, and it starts in part with diversifying medical literature.

Historically, Western academic publications depict white bodies—specifically, white men—in their illustrations the vast majority of the time, making able-bodied, Caucasian males the default for trained illustrators.

These professionals are part of the Association of Medical Illustrators, and there are fewer than two thousand globally. In America, this specialized field has typically been made up of people who are also white and male, which has directly impacted the bodies portrayed in learning materials.

This lack of equitable representation matters because it can have implications on both practitioners and patients.

For providers, the perpetual use of white, able-bodied patients in textbooks creates limitations in their abilities to accurately diagnose and treat people who represent other demographics. For example, in dermatological education, lighter skin is the norm when conducting clinical trials; doctors often misdiagnose medical issues such as rashes, lupus, and even skin cancers for individuals with darker-pigmented skin.

Furthermore, because of a gap in knowledge, practitioners may rely on racial stereotypes or generalizations (like, Black people have a higher pain tolerance or thicker skin than white people) instead of offering care specific to the patient, due to a lack of exposure to darker skin tones in training and understanding of how conditions affect these individuals differently.

For patients, a lack of diversity can cause feelings of being excluded and unacknowledged in a health care setting, which can lead to mistrust when receiving preventative care and choosing to maintain treatment. A 2008 survey revealed that only 43% of Black patients trust their physician compared to a reported 80% of white patients. Such reluctance, in turn, yields negative health consequences that can be life-threatening even when the cause of diagnosis is preventable and curable.

This is why it’s crucial to avoid implicit bias by including more nuanced illustrations that showcase the particular issues affecting marginalized populations. Depicting conditions common to these communities will better educate medical professionals and establish trust with patients of all demographics.

Since his viral image, Ibe has been invited to have some of his work published in a clinical handbook designed to show how a range of conditions appear on dark skin, which serves as a small win in the pursuit of equal representation.

While the depiction of a Black fetus may have been a departure from what’s considered commonplace in the world of medicine, we surely hope it’s far from the last, and that diverse skin tones in medical illustrations will become routine.