The Effects of the US Childcare Crisis on Parents

More than 3,000 parents told Pregnancy & Newborn how the problem has impacted their lives.

“We are going to feel so rich.” This is something my husband and I would enthusiastically say to each other on a regular basis during the countdown to our oldest daughter starting kindergarten—because soon enough we’d have an extra $1,000 to our names every month. By the time her first day of public school arrived, we estimate that we had spent more than $52,000 on her childcare. And this is the total cost for just one of our two kids.

And we are lucky. That is less than the average cost of childcare in the U.S., which is over $14,000 annually. Parents all over America are spending tens of thousands of dollars on childcare every year—assuming they’re even able to get their children off waitlists and into a facility. In fact, it costs less to send a student to an in-state public university for a year than it does to send a child to daycare for the same amount of time. Even worse, the cost of childcare in the U.S. is more than the cost of housing in most of the country.

It’s a well-known fact that the childcare system in this country is broken, but no one seems to be doing anything to fix it. And until the problem is solved, parents will continue to ask themselves questions like, is my take-home salary after paying for childcare worth it? Is this facility that I don’t trust my only option because everywhere else has a waitlist? With the cost of daycare, can I afford my dream of having more children?

At Pregnancy & Newborn, we wanted to know how the childcare crisis is affecting our readers, so we surveyed them to find out. We received more than 3,000 responses from parents sharing their personal experiences with childcare in America. And while analyzing data, one thing became abundantly clear: The current situation is completely unsustainable.

Why Is US Childcare in Crisis?

The COVID-19 pandemic brought both school and daycare center operations across the country to an abrupt halt. As millions of parents worked remotely (if possible), were furloughed, or laid off, school-aged children in America were left without classrooms, and families entered the unknown journey of remote learning. But there was no virtual option for younger children. So while parents logged onto their laptops and their daycare centers shut down indefinitely, caregivers learned to juggle a new reality no one was prepared for. Then, as the world finally began to open up again and restrictions were lifted, parents were expected to return to the office—but schools and daycare centers remained closed.

Mothers began to leave the workforce in droves in order to stay home with their kids because many employers couldn’t (or wouldn’t) give them the flexibility they needed to both work and care for their children simultaneously, nor could they justify paying a private babysitter the equivalent of their own salary just to go to work. The experience of the pandemic brought the childcare crisis to light, but the cracks in the (now crumbling) industry have been forming for years.

In most developed countries, early childhood care is guaranteed and either generously subsidized or entirely free. In the U.S., however, it is mostly privatized, with the government offering a minuscule childcare tax credit to families with children under the age of 13 years old and minimal additional help to families they deem “low income” or “very low income.” This means most parents have to cover tuition costs almost completely on their own and fight to get their child a spot in a preferred facility or program.

The problem is that the demand for these coveted childcare spots is high, but the supply is low. Because of this, costs continue to rise and parents have no choice but to either pay unbelievable rates for adequate care, pay less (but still a lot) for possibly compromised childcare, or leave the workforce entirely. No matter what, it puts a significant strain on families.

The cost of childcare

Arguably, the biggest problem with the childcare industry in the U.S. is the cost. In 2022, the average monthly tuition for an infant in daycare is $1,230, and according to the U.S. Census, the median monthly income for a family in 2020 was $5,627 ($67,521 annually) before taxes. This means, on average, families spend nearly 22% of their gross income to send just one child to daycare.

One survey respondent, a mom of two in Indiana, had to get very creative to make up for this astronomical cost. “When my daughter was younger and I couldn’t afford childcare, I rented a room out of our house on Airbnb.”

Unfortunately, this story isn’t unique. Childcare costs are plaguing families all over the country; 58.2% of our survey respondents said they pay $500 or more every month in tuition for one child. To break it down further:

- 44.7% pay $750 or more

- 29.8% pay $1,000 or more

- 18.5% pay $1,250 or more

- 11.3% pay $1,500 or more

Even in a two-income home, some families can’t afford the rising costs of childcare and are accumulating debt just to make ends meet. A Virginia mom of a 4-month-old said full-time daycare costs more than $1,500 per month where she lives, and it’s crushing her family financially. “Both [parents] have to work, but we still don’t make enough to cover the cost of childcare. We take a loss every single month, but it would be worse with only one income. It’s truly not sustainable.”

Most families aren’t having more children because of the cost, or lack of availability of childcare. When we asked, “Would you like to grow your family, but can’t/are hesitant to because of the cost/availability of childcare,” 61% of respondents said yes.

A mother of one 8-month-old in Westminster, Colorado, told Pregnancy & Newborn, “Childcare costs more than our mortgage every month. We’d love to give our child a sibling, but there is no way we could afford it. At $1,775 a month [tuition] for the infant room, we’d be paying over $3,500 [per month] for two children … Sadly, another child is out of the question for us financially.”

This isn’t a problem that is only disproportionately hurting lower-middle class or poor families. Middle-class, double-income American homes are also affected by the exorbitant cost of daycare. If it’s affecting the middle class, you can just imagine what it is doing to lower-income families. “My spouse and I make decent money, but I would have to quit my job if we decide to have another child (which we want) because childcare will cost more than what I make,” said another mom who has a 2-month-old and lives in Vancouver, Washington.

The accessibility of childcare

Cost is only part of the issue, though. There’s also a major problem with access to childcare—especially post-pandemic.

Between January 2020 and January 2022, the childcare industry lost around 120,000 workers. These jobs are notoriously high-stress and low-paying, despite how much parents pay in tuition. This fleeing of childcare workers combined with the national labor shortage (which has greatly impacted the childcare industry) leaves childcare centers scrambling to employ enough teachers per classroom to meet their mandated teacher-to-student ratios.

Simply put: Childcare center enrollment allotment is directly correlated to teacher headcount. So, if there’s a shortage of teachers, it creates a serious demand problem for the childcare industry. Because of this, classroom waitlist times across the country are shockingly long.

“We had to start looking for childcare before we even told our families we were pregnant,” a mom-to-be in Dunn, North Carolina, told us in her survey response. “We are currently on a waitlist for childcare and have been for six months. It will be a total of nine months when [a spot] is available.”

In fact, 80% of survey respondents said there are currently waitlists of six months or longer in their area; some as long as two years.

A mom of two with another on the way in Fletcher, North Carolina, ultimately had to leave her job because daycare waitlists in her area were so long after COVID-19 lockdowns. “When restrictions started to lift, I had planned to go back to work, and although childcare facilities had reopened, there was a lack of employees and we were unable to get in. We’ve been on waiting lists for over a year.”

Quality of care and satisfaction

We all know that not every childcare facility is created equal. Some offer a formalized, full-day, early childhood, and pre-k curriculum, while others simply provide a safe, supervised space for kids to play throughout the workday or a “mom’s morning out” format that is focused more on giving parents a couple of hours to themselves a few times a week rather than educating children. There is a need for all of these types of facilities, but if you’re seeking one format and only have access to the others, it feels limiting. Parents in these situations are left having to compromise what they want for their children, paying far more than they can afford, and/or not feeling comfortable with the people they are leaving their children with.

For many parents, this stressful compromise means having to supplement their children’s care with an additional form of childcare, resulting in even more tuition or paying a babysitter’s salary. When asked if they have to supplement their child’s care, 40% of survey respondents said yes.

A mom of two children in New Jersey told Pregnancy & Newborn that before her job went remote during the pandemic, she was spending more than $2,500 per month on childcare for her 3-year-old and 8-year-old. Between her oldest son’s regular school and aftercare hours and her youngest son’s limited daycare hours, she had to hire a babysitter for morning and evening care. “I had to be on a train to Manhattan early in the morning, and even if I left the office before 5 p.m. every evening, there were times I wouldn’t make it back in time for pickup. To make it work, I had to hire a babysitter to come to my house in the morning, get my kids ready, and drive them to school and daycare. At the end of the day, she would pick them up, bring them home, and prepare dinner, so I could finish my workday without having to worry about racing home before daycare and aftercare closed. My husband and I were spending a fortune between daycare, elementary school aftercare, and a babysitter.”

Even for parents who don’t have to supplement their child’s care with additional childcare, they’re often not getting what they pay for in a post-pandemic world. A Longmont, Colorado, mom of a 20-month-old said, “I’ve received many emails from my daughter’s daycare at various times asking parents to keep their children home if possible because they didn’t have the right amount of staff for the day. As a single mom, my income is the source of our livelihood so I can’t do that. So the whole day I’m anxious because I know [the school] needs more help. I feel incredibly guilty and worried about her all day.”

Effects on Working Parents

Between February 2020 and March 2021, there were 1.4 million fewer moms of school-aged children in the workforce than in the year prior. It’s no surprise that the pandemic left so many parents with no other choice but to leave work—given that schools suddenly shut down and someone needed to stay home with the kids. However, by the time most schools reopened in 2021, 46% of the moms who were still unemployed had left the workforce due to childcare issues. In fact, lack of childcare was the number one reason moms left or changed jobs in 2021.

The central issues of the childcare crisis extend beyond the childcare industry itself. Employers also play a major role. Lack of work-life balance, childcare tuition assistance, cost of living wage increases, and flexibility also factor into the problem.

A little over half of U.S. employers offer some kind of childcare assistance, but they usually come in the form of a low-maintenance, inexpensive benefit like Dependent Care FSAs. While these programs are a nice perk, they simply provide parents with tax benefits up-front (rather than when they file the following year), so there is no real investment from the employers.

The number of employers who provide employees with childcare benefits outside of Dependent Care FSA programs is significantly lower.

According to Society for Human Resource Management, by September of 2020, six months after the start of the pandemic, only 9% of employers were providing or considering providing childcare subsidies to their employees, and only 7% were providing or considering providing on-site childcare. These numbers are shameful in general, but especially so when you consider that 46% of family households in the U.S. have two working parents. It’s no wonder why the negative effects of the childcare crisis have extended into our economy and contributed to the labor force shortage America is currently facing.

America’s workforce

The cost of tuition and the labor shortage’s effect on the childcare industry specifically is having a ripple effect on America’s workforce as a whole—exacerbating the challenges of “the great resignation.”

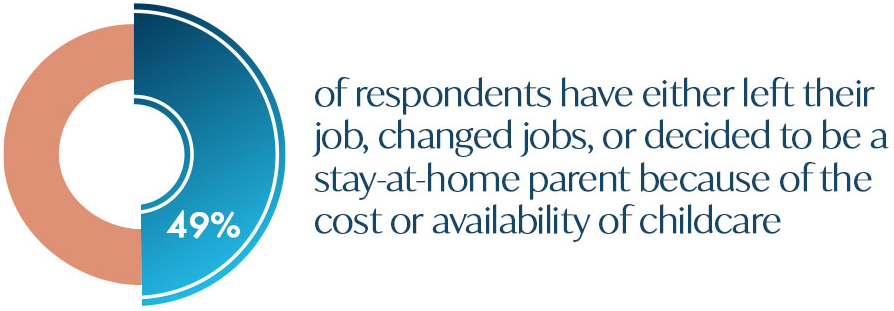

In our survey, when asked, “Have you left your job, changed jobs, or decided to be a stay-at-home parent because of the cost or availability of childcare,” just under half of our respondents said yes.

Even more appalling, 77% of respondents who are not currently working said they would return to the workforce if childcare was more affordable or more accessible.

Employer flexibility

“We literally have no other option but to have my mother stay with [my son] during the day,” said a mom to a 24-month-old in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, “When my mother was sick she couldn’t take care of him, so I had to stay home. I was accused by my boss of lying to take off of work for what she suspected were interviews.”

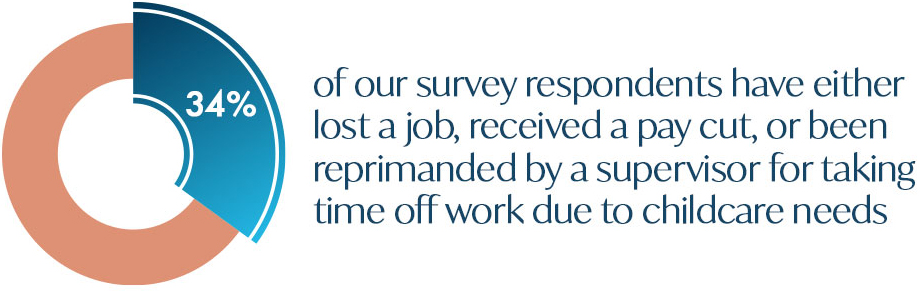

While this story is absolutely infuriating, what’s even more aggravating is that she’s hardly alone in her experience. Sadly, 34% of our survey respondents answered yes to the question “have you ever lost a job, received a pay cut, or been reprimanded by your supervisor for taking time off work due to childcare needs?”

All working parents are feeling the pains of the childcare crisis to some degree, but those who are working for employers that offer flexibility are able to manage things a bit easier. In a 2021 survey of working moms, 55% said having a flexible work schedule “significantly relieved” some of the pressures on working parents—specifically the ones that were “exacerbated by the pandemic,” such as inaccessible childcare.

Lack of Public Policy for Childcare

People and organizations have been lobbying for the federal government to offer some kind of support for childcare for decades. Advocates have been fighting for it since before World War II, and the Democrats even included a Universal Pre-K program in their 2021 spending bill, which would have provided free preschool education to 3- and 4-year-olds, and would have increased childcare worker salaries, but it was ultimately removed for lack of support/funding.

U.S. parents aren’t totally on their own, though, because the federal government offers (minimal) help with the cost of childcare through tax credits. Parents can get a credit on their tax returns to help offset the costs of up to $1,200 for one child or $2,100 for two or more children in daycare. Unfortunately, as we all know, a credit this small won’t even cover a single month of the national average cost of childcare for most families.

“How can the U.S. government expect this economy to keep thriving when families are struggling to get basic needs fulfilled,” a mom of a 2-year-old in San Francisco, California, wrote in a survey response, “Everyone deserves access to quality childcare—and those workers deserve to be compensated with salaries, benefits, and all of the protections of any other care provider (e.g. doctors, nurses). They are essential and so underpaid.”

A mom of two children living in Jersey City, New Jersey, said she is among a number of mothers who left the workforce due to the rising costs of childcare. She’s now a stay-at-home mom because, “The amount of money I’d make in a year is equal to or less than what it would cost me to afford two children in daycare, so I gave up job hunting and I am now unable to pursue a career,” she explained. She also highlighted that, in addition to the lack of support for childcare, the U.S. also doesn’t provide universal paid family leave (making America an embarrassing outlier compared to every other developed country). She said, “In a country without maternity or parental leave, childcare should be affordable and accessible to every new parent. It’s absolutely ridiculous to live in the world’s richest nation and feel this helpless.”

The lack of paid family leave adds more pressure to the childcare crisis because parents have to scramble to find centers with room for their infants so they can return to work. Also, since most maternity and paternity leave is unpaid, parents are not only asked to cut their bonding time with their new baby short but to also shell out thousands of dollars after going unpaid for weeks or months.

In our survey, only 47% of parents said they were eligible for some kind of paid family leave through their employer. And when they were asked if they felt like they had enough time off to heal physically and emotionally bond with their newborn before returning to work, 80% said no.

Not to mention, required teacher-to-student ratios in infant rooms are the smallest, which means these programs usually incur higher costs (in most daycare centers, the rule is the smaller the class ratio, the higher the price).

A Knoxville, Tennessee mom of a 4-year-old and a 3-month-old, said waitlists for infant programs are more than a year out, so people in her area have to try to reserve childcare before even trying to conceive. On top of that, she said the cost is so high she can’t afford it, and government assistance is reserved for the lowest-income families. “When I had my first daughter, I had the [government] assistance and still struggled to afford groceries or basic needs. I have gone into mountains of debt trying to pay for childcare.”

Because the flaws in our childcare system have been ignored for so long, we’d need a multipronged approach in order to truly get it to a place where teachers are paid a living wage, parents can access and afford care, and where kids are getting the best education possible (think: sweeping reform). Unfortunately, change takes an excruciatingly long time in our government, but you can push for it yourself by contacting your representatives and voting for candidates who include childcare policy in their campaign promises. It shouldn’t and it doesn’t have to be this way.

Pregnancy & Newborn would like to thank the 3,087 parents who participated in our survey. Your input is valued and we appreciate your willingness to share your stories with us.